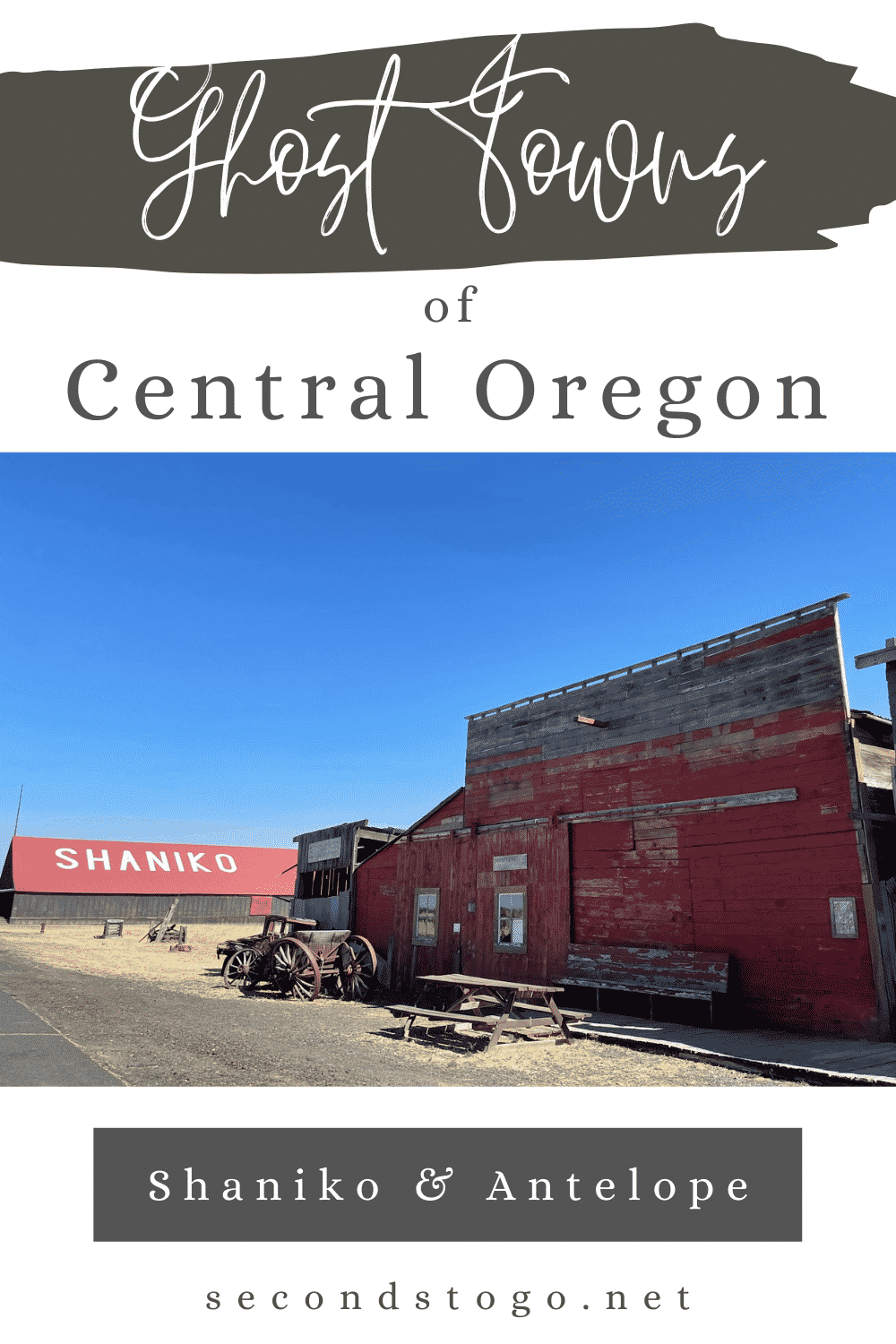

Shaniko and Antelope are 2 American towns often labelled as ghost towns in central Oregon, but are these communities really abandoned relics of the old west or is it all a scam? We set out expecting to find a hollow remnant of what once was while visiting Oregon. Instead, we found something else.

Table of contents

Ghost Towns in Central Oregon: Early History of Shaniko

Shaniko and Antelope have an interlinked history, but Antelope has seen much more controversy over the years. Outlining their history separately will keep things simpler.

Shaniko, which is currently located along highway 97, was once a larger town than Bend, and the largest wool shipping center in the world in the early 1900s.

Shaniko essentially began as a small town called Cross Hollows. Cross Hollows was a crossing point for all the traffic through the interior part of Oregon. Here, travelers and stage lines passed through on the Dalles and Canyon City Stage route.

While the town was officially known as Cross Hollows, it wasn’t uncommon to hear locals use the nickname of Shaniko, a much simpler way to pronounce the name Shernekau. That’s because, in 1878, A. Shernekau established a homestead in Cross Hollows, and built up a town that included a hotel, blacksmith shop, store, saloon, and post office.

Soon, Shernakau sold the entire town to William Farr. With nearby Antelope growing along the same route, Cross Hollows seemed to die out. Farr packed up his things, and moved himself, and many of the buildings in Cross Hollow to Antelope.

In 1899, a railway line from Biggs to what used to be, Cross Hollows was announced, and Shaniko came into fruition. Prior to the railway, freight was brought across interior Oregon by 6-12 team horse stagecoaches. As imagined, the journey was long and arduous, so the introduction of the railway, especially a line that terminated in Shaniko, meant big progress and big growth.

Soon, goods were being transported into the tiny village for distribution across central Oregon. The Shaniko post office and town hall were erected in 1900, the same year the first railcar rolled into the terminus, and the town was officially incorporated in 1901 as Shaniko.

Shaniko’s Railroad Boom

In 1899, long before Shaniko would be heralded as a ghost town in central Oregon, The Shaniko Warehouse Company filed paperwork to build a warehouse, and by 1901, a 75,000 square foot building was available to process the freight coming into the railroad station.

In the first couple years of the 1900s, Shaniko had about 300 residents most living in tents while the shearing pens, cattle pens, sheep pens, and other amenities necessary to handle livestock freight were constructed. At this point the town had a doctor, saloon, general store, and warehouse.

A 1933 edition of the Bend Bulletin newspaper states that the Sanford’s Cash Store sold general goods and groceries, and the Reception Saloon sold alcohol to thirsty patrons.

In 1902, the Columbia Southern Hotel, now called the Shaniko hotel, was constructed. By 1904, Shaniko was the largest wool shipping destination in the world. Despite its growth and prosperity, however, Shaniko was quite dangerous.

In fact, gambling houses and saloons were popping up everywhere, and the Shaniko jail, located in the City Hall, was always full. By some accounts, the town did not even have an official cemetery and simply left the poor souls who overdosed on alcohol or died from gun fighting out in the open as coyote food.

Despite its dangerous reputation, the population of Shaniko neared 600 residents by 1910, and the town covered 30 blocks. However, Shaniko’s growth trajectory was about to come to an end. In 1905, several railway businessmen took an excursion from Shaniko to Farewell Bend to explore the feasibility of extending the railway line beyond the town terminus. This undertaking essentially sealed the fate for Shaniko, but no one knew that yet.

A July 1960 edition of the Bend Bulletin states that for over a decade Shaniko had been “the end of the rails,” serving as a stopping point that controlled the flow of goods to over a dozen surrounding counties. Merchandise would come into Shaniko and then be transported to surrounding communities by wagon load. By extending the line beyond Shaniko, surrounding towns could receive goods faster and more economically.

In 1911, the railway leg from Shaniko to Bend became a reality. Goods that were once unloaded and shipped from Shaniko now continued onward directly to Bend, beginning the decline of the heyday of Shaniko.

Soon, many Shaniko residents moved and found their way to Bend in search of money from timber claims, and Bend began growing at a rapid pace. Bend, which received its first electric lights in 1910, became everything Shaniko was, and more. The new rail line, however, was not to be the only turning point from prosperity to potential ghost town in central Oregon. There was more to come.

The Hood River Glacier Newspaper reports in April 1921 that the State Highway Commission decided to build a highway from Biggs to Shaniko called the Sherman Highway, as well as a second highway named the Dalles- California Highway from Shaniko to Criterion. The highways would offer an additional means of transporting goods around central Oregon, something that could further impact Shaniko on its way to decline.

As a result, the addition of a secondary rail line in 1942 that paralleled the Shaniko line but ran farther up the Deschutes River and made its way all the way into California, was just more bad news for the fading town. With larger freight loads utilizing the new and longer railway, and smaller loads using the highway, the Shaniko railway and station saw a large decline in traffic.

To add insult to injury, a large fire in 1910 had consumed much of the town’s business district. According to The Capital Journal out of Salem, the blaze began in the Central lodging house before quickly spreading to the nearby California wine house, the Silvertooth and Browder’s saloons and the Wilson drug store. Smaller structures were also destroyed by the rapidly ensuing flames.

With much of the town destroyed and many farmers utilizing highways to transport their goods to the larger Deschutes line, rail service to Shaniko was stopped in 1950, and soon, most of the railway line north from Shaniko was removed.

The Shaniko Gang Comes to Town

Hoping to preserve the town’s history, Sue and Joe Morelli purchased the Shaniko Hotel in the 1950s. Joe Morelli worked hard to find antiques and create a museum for the town, an establishment which soon came to include antique wagons, stagecoaches, and other staples of early rural life.

Joe and Sue had the goal to create a tourist destination and preserve many of the buildings still standing. But in 1960 the general store closed and its goods were liquidated. In 1963, the town had a population of 39, and the town hall was to be sold for destruction, while the long-abandoned schoolhouse sat covered in weeds.

With few visitors to the town, Sue turned many rooms of the Shaniko hotel into a foster home for the elderly and mentally handicapped, who she affectionately named her Shaniko gang. At its peak, her Shaniko gang consisted of 30 members.

Unfortunately, the Shaniko gang was forced to disband in 1977, when Sue was required to sell the hotel due to lack of funds to bring it up to code. Shaniko’s once revolutionary water system which piped water from a canyon to the south was outdated and under pressured for the sprinkler system, now required by code to make the hotel safe.

Sue and Joe left their beloved Shaniko while many members of the Shaniko gang were placed in elderly care homes.

The hotel, remaining antique memorabilia, and all owned by Joe and Sue were auctioned off to Earl M. Bone for $54,000. Earl had plans to restore the hotel, but the plans did not come to fruition.

Oregon Ghost Towns in Central Oregon, a More Recent Past

The Corvallis- Gazette Times reports in February 1988 that Jean and Dorothy Farrel had purchased the hotel and other sections of the town in 1985. The Farrel’s invested $300 thousand into the hotel, and created an RV park and new shops. They worked hard to update the hotel with new wiring, plumbing, floors, and a new septic system.

A 1993 edition of Salem’s Statesman Journal reported that most of Shaniko was modern, with the exception of the hotel. They also stated that the wedding chapel and store fronts were of more recent build, and essentially constructed for tourism.

By 2000, Shaniko had a few dozen residents. In that same year Robert B. Pamplin, one of Oregon’s wealthiest men purchased the Shaniko Hotel, RV park, and the strip of road with the storefronts.

Pamplin faced a water dispute over the land in 2008, forcing him to close the RV park. He then put the land up for sale, before taking it off the market in 2016.

Today, in 2022, the hotel is currently closed, with no information released as to its opening. Shaniko Days, a festival in the town every summer, has not happened since 2019. Many are hoping for a return post pandemic.

There are public bathrooms, an ice cream parlor and an antique shop that are open with limited hours and seasonally.

The question that remains is whether Shaniko fits the bill of a Ghost Town in Central Oregon. We’ll have more on that later, but first, let’s explore the controversial history of nearby Antelope.

The Early History of Antelope- A Soon to Be Ghost Town in Central Oregon

Unfortunately, Antelope’s early history is less recorded than that of Shaniko. The best record of the early days of Antelope is the Dallas Times Mountaineer Newspaper.

An 1898 edition explains that Antelope came to be in the 1860s. Back then, Antelope was a trading point for those traveling along the path through interior Oregon, similar to the early days of Shaniko, but it seems Antelope is older.

Antelope began 2 miles from its present location but was shortly moved to better serve the “road” at the time. In 1898 Antelope was praised as being “the most important Oregon town for its size.”

In this same year, Antelope was the site of the largest sheep operation in the state and transported the most wool. This is the most likely factor to explain why the railway was established in nearby Shaniko, which was a bit easier to access when it came to building a railway.

The 1898 Antelope boasted 2 general stores, a drug store, a physician, a surgeon, blacksmiths, 3 saloons, 4 large hotels, stables, a barber, a printing office, a meat market, and a post office.

In this era, when Shaniko was essentially non existent, Antelope was the place to be. Antelope had a reputation for clean cut men who traded and conducted business in a fair way.

In 1900, when the first railcar rolled into Shaniko, Antelope began shrinking. Many residents and businesses traveled the roughly 8 miles to set up in Shaniko.

When Shaniko began to dwindle, Antelope did as well, with only stalwart sheep and cattle farmers remaining steadfast in their town.

When Highway 97 was built through Shaniko, the population of Antelope dwindled further. This left the area of Antelope proper a near ghost town in Central Oregon, but when a paved road was built in 1957 from Highway 97 to Antelope, it connected the small town to the rest of the world.

For many years, the residents of Antelope lived quietly and happily away from the busyness of the remainder of the world. That is, until massive upheaval hit the town in the 1980s.

Repopulating a Near Ghost Town in Central Oregon

In the early 1980s, Antelope saw a calculated and precise take over by a religious sect, that has been often called a cult in more modern times.

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh was an Indian religious leader who preached the concept of dynamic meditation. He quickly began to amass a following in his native India. Unfortunately, his teachings put him in conflict with the Indian government, leading him and his followers to flee to Oregon.

In 1981, Bhagwan purchased a 100-square-mile ranch once called the Big Muddy Ranch, a few miles outside of the city of Antelope. Rajneesh soon had two to three hundred followers join him at the ranch. The goal was to create a city named Rajneeshpuram at the ranch and become incorporated.

Rajneesh and his followers worked hard to farm the desert land and turn it into an oasis. Followers, who were often called disciples or sannyasins, worked 80-hour weeks on the ranch for little or no pay.

But their hard work paid off. Soon the ranch had a 330-million-gallon lake/ reservoir, a shopping mall, medical clinic, hotel, and living quarters.

The cult brought in money by working the ranch, and from the Rajneesh International Mediation University, which offered courses from $80- $7500. In fact, the ranch commune brought in hundreds of visitors daily, many who wanted tours of the commune and the university. Bhagwan at one point owned an airstrip, 90 buses, 4 airplanes, and 40 Rolls Royce, which he used to transport people to and from the ranch.

In 1982, Rajneeshpuram received its incorporation, despite much controversy. Soon, locals and people across the state began to question the incorporation status and the land use regulations of the city.

The basis behind this was the fact that the Rajneesh people were using an agricultural area to create a commercial center, which threatened future farmland use and opened the door for other areas to turn designated farmland into metropolis regions.

When the Rajneesh followers were faced with losing their incorporation status, things got bad quickly. The followers soon waged a political takeover of the nearby town of Antelope.

The Rajneesh people signed up to vote in the 1982 Antelope election. At the time, an Oregon law made it legal to establish residency and register to vote as late as election day.

As they voted, each Rajneesh follower simply wrote in the name of a Rajneesh leader to fill the city positions up for grabs, and then cast their vote accordingly. Given that residents of Rajneeshpuram outnumbered the long-time local residents, it was easy to hijack the election.

It wasn’t long before the outnumbered residents of the town felt threatened and began selling their homes and moving elsewhere.

BY 1983, 15 non-Rajneesh residents remained in the town. Meanwhile, Rajneesh members owned most of the real estate, and even took over the restaurant, turning it into a Bhuddist vegetarian eatery. Worst of all, it seemed they were destined to employ a reign of terror on remaining town residents.

Rajneesh followers would run car patrols up and down the streets of Antelope, while the remaining residents lived in fear, but stubbornly refused to give up their homes. During this time, the Salem Statesman Journal records Oregon resident Alice Hensley as saying: “There was a period of time when I thought, “if someone knocks on my door at 2 o’clock in the morning, I’m going to fire through the door.”

Many homes were left abandoned, as the takeover had driven real estate to an all time low in the town, and some houses could not be sold. Outside of Rajneeshpuram, it seemed that Antelope was destined to become a ghost town in central Oregon.

The Great Antelope Name Change

As Rajneesh and his followers gained greater control of Antelope, they managed to elicit a name change, christening their new town the City of Rajneesh. Residents soon opened up a vote to unincorporate Antelope, so the Rajneesh would lose their power, but the vote failed.

However, in 1983, the county ruled that the city of Rajneeshpuram was in violation of land use laws, and that no more building permits would be issued for the city. And in June of that year, the county pulled the incorporation status of the ranch.

By 1984, Wasco County dropped Rajneeshpuram from the county’s comprehensive land use plan, which majorly angered Bhagwan’s followers. These new developments seemed to reignite the war again.

The mayor of Rajneeshpuram was reported by the Statesman Journal in July 1984, as saying “what I see here today as I look out is the beginnings of civil war in this country.” He also said that he thought the only way to avoid conflict and relieve tensions was for non Rajneesh people to accept the religious sect and their control, but also said, “we’re ready for war, if war comes.”

One reason for the escalating tensions seemed justified as Rajneesh followers took control over the public school, turning it into a religious private school that was funded through state education monies. As non-Rajneesh town residents began fighting for permission to send their children to school in nearby Madras, the state launched an investigation. It was found that the school was employing Rajneesh followers with no teaching degrees, and these teachers were wearing their religious garments while teaching.

An Oregon law at the time stated that teachers in public schools could not wear their religious garments while teaching, due to the mixing of state and church. The Rajneesh city council soon made the decision to use qualified teachers and have the religious members hide their necklaces under their garments.

Much to the dismay of the non-Rajneesh citizens, this agreement satisfied the state’s requirements, and funding was returned.

Rajneeshpuram Strikes Again

1984 also brought many lawsuits filed against the Rajneesh people, including those related to false immigration status and sham marriages for the sake of immigration. Under pressure from all sides, the people of Rajneeshpuram launched a bioterrorist attack against the state of Oregon.

Prominent followers of Rajneesh purposefully spread salmonella in 10 restaurants in the Dalles Oregon area. As a result, around 750 people became very ill.

This was an attempt by the Rajneesh people to incapacitate the voters, to gain political control of Wasco County. At the same time, the Rajneesh Humanity Trust was bringing in thousands of new members, by providing homes to as many as 3,300 homeless people. This was not done as a humanitarian effort but rather an attempt to gain more voters on their side.

Soon, the eligibility of these voters was called into question, and every member was required to face a hearing about their eligibility. Many of the transient people who had once been given refuge soon found out that voter registration cards had been turned in on their behalf, without their permission, and full of inaccurate information.

As a result, many of the new recruits did not want to stand up to these hearings, and instead left the commune in droves, flooding nearby cities. The Rajneesh people would often drop them off in haphazard locations without any regard to their wellbeing or safety.

One man died of exposure near Mount Hood after being given a mind-altering drug at the Rajneesh medical clinic, before being dumped outside at a Government Camp.

By 1985, the cult had dissolved and mercifully left the area. Bhagwan Rajneesh was arrested and deported upon taking an Alford plea to crimes involving immigration fraud and arranging sham marriages for the immigration status of his members.

Higher up members of the cult were arrested and jailed for crimes such as arson and attempted murder, immigration fraud, voter fraud, and drug smuggling.

Soon, the rightful residents of the City of Rajneesh voted to return the name to Antelope, and the ranch was auctioned off due to foreclosure. To close this chapter of Antelope’s history, the Rajneesh corporations were required to pay over 5 million dollars in restitution to the people and businesses that were hurt in the salmonella attack.

Today, the Young Life, a Christian organization operates the Washington Family Ranch from the location of the Rajneesh compound. Two summer camps take place there each year, and the Big Muddy Ranch airport is still standing.

Still, the town of Antelope has not completely recovered. Driving through the streets you will see abandoned buildings, remnants of the past and many signs warning of video surveillance that serve as a reminder of the tension and fear that once held this town hostage. Antelope is working to shake its reputation from the past, and its current reputation of being one of the ghost towns of central Oregon.

What Defines a Ghost Town in Central Oregon?

The oxford dictionary defines ghost town as “a deserted town with few or no remaining inhabitants.” My biggest question with this definition is what is a few? Typically that would mean 3-4, but does the definition of “few” change when defining a ghost town?

CityData.com considers a “very small town” in Oregon to be under 1000 residents. Would under one thousand residents be considered a few?

I decided to keep digging on this definition.

Wikipedia defines a ghost town as an “abandoned village, town, or city, usually one that contains substantial visible remaining buildings and infrastructure such as roads.” It also states that a town often becomes a ghost town as the economic activity that supported it leaves the area or simply fails.

A ghost town can also result from a natural disaster, such as flooding which can destroy buildings. In one rare case, a continuous fire burning in an abandoned mine underneath the city prompts the eventual evacuation of all residents. This is the Case in Centralia Pennsylvania.

I did find that Wikipedia states that Centralia, for example, is a “near-ghost town.” The 2010 census for Centralia stated the population of the town to be 10 people which dwindled to 7 in 2013.

In this case, we can assume that in the definition for ghost town above, few does mean “few.”

If this is fact, or close to it, we can assume that both Shaniko and Antelope are not true ghost towns. Shaniko has a current population of 30 based on the 2020 census. And antelope has 249 residents, also according to the 2020 census.

So, in the end, Antelope and Shaniko are not truly ghost towns by definition. Despite their ghostly reputations, you may want to read on before driving the long and lonely highway in search of old abandoned villages.

Shaniko and Antelope, Ghost Town or Scam?

Our trip to Shaniko and Antelope was filled with some apprehension. Would we be safe there, in an abandoned town? Was this town really abandoned? Is the drive worth it?

Our journey from The Dalles down to Shaniko led us under and next to miles and miles of electric lines that power many interior towns and cities of Oregon.

Mom remarked how creepy they were to her. “Almost apocalyptic,” I mentioned. It was a similar feeling I got when seeing the large wind power windmills on my first trip out west.

We chatted as the dog laid passed out in the back seat, blissfully unaware that the further we traveled, the more nervous we got.

For one thing, we had no cell service. What were we to do if we had a flat tire, ran out of fuel, or needed any other help? In hindsight we probably should have followed the much more populated Highway 97 to Shaniko, but by the point we’d traveled miles down the lonely winding road, seeing only two other cars, it was too late to make that decision.

Before we could entirely panic, the desolate road suddenly opened up to another road. This one, rather than being empty, was full with the hum and whooshing of semi trucks traveling at 60 mph.

So strange, to be nowhere, with no one around, and then suddenly be here. This must have been how the folks of the early 1800s felt when traveling this same way, back when it was Cross Hollows and Antelope, before Shaniko existed.

Suddenly, feeling much less apprehensive, we turned left towards the Shaniko sign. Highway 97 quite literally skirts the exterior of tiny Shaniko, so close that you could most likely feel the rush of traffic while standing at the ice cream parlor.

Wait, why is there an ice cream parlor in a ghost town? Sure, maybe an abandoned one, but not one with an open sign and an immaculate ice cream cone flag waving outside. Strange.

Shaniko’s streets are wide. The main ones seem to mimic the old west town roads, which were stated to be 100 feet wide. We crept along these quiet streets with the sound of trucks in the background. The contrast felt strange.

Besides the ice cream parlor, the town sure looked ghostly. A few trailers and mobile homes sat tucked back behind some antique looking buildings. It sure looked like a ghost town, but didn’t feel like it.

Upon driving a few laps, some photos, some confusion, and some frustration, we came to the conclusion that Shaniko is a bit of a tourist trap, using the history for a draw.

It seems that the only authentic building from Shaniko’s heyday is the hotel, which sat closed and dark on our visit. I have no doubt that many of the artifacts spread throughout the town are authentic.

Perhaps, some of the wagons, some of the antique looking tools, but certainly not the too new western facades, with minimal damage despite having supposedly sat empty in the desert for 100 years.

I think Shaniko is a product of its past, a town who grew too quickly, and then faded, leaving the past the only thing the name Shaniko could hold onto.

Over the years, many people tried to save Shaniko, bring in guests, visitors, tourists. This effort has worked on some smaller levels, but in the end, I think Shaniko itself, and many of the residents are okay living with the past.

On to Antelope

The eight-mile drive to Antelope had mom filling me in on the uneven history of the town. In my head, I was envisioning abandoned commune buildings and not a soul in sight. In contrast, before entering the town, we saw signs for a few different ranches, some cars, and plenty of signs of habitation with only a few abandoned places.

The first building that drew our attention was the empty school building, the same one taken over by the Rajneesh people. The mint/ yellow colored facade had a few cracks in paint and an overgrown playground.

But overall, the building looked usable, and it turns out it is. The building no longer operates as a school, but is used as a community center.

Delving deeper into the town, we saw a few boarded-up buildings, some in more disarray than others, but no more than any other tiny town across the United States.

Soon, we began noticing that most of the occupied houses boasted cameras and security systems, announcing to all visitors that they are being watched.

Now, this may be a remnant of the effects of the Rajneesh people, but mom and I tend to be a bit cautious on our adventures. We would never want to intrude upon people’s land or make anyone feel uncomfortable.

So, we considered another possibility. Maybe the signs were due to the recent popularity surge of of ghost towns in central Oregon. Many articles had recently popped up falsely claiming Antelope to be a ghost town. That reputation may be one Shaniko embraces and perpetuates, but Antelope does not.

Especially considering the history, it is not surprising that the Antelopians want to live their lives their way and in privacy.

As we drove around Antelope, I couldn’t help but say, “this is just a small town. Have some of these people online never seen a small town before?” And to be honest, I think that may be the fact.

Growing up in New England, I experienced many tiny tiny towns on our drives. Some of them with abandoned and falling buildings, but yet, we consider them small towns, and not ghost towns.

With a population of 250, and plenty of occupied homes, Antelope is just that, a very small town, not a ghost town.

How to Get to Shaniko and Antelope

When visiting Oregon, getting to the ghost towns of central Oregon that are Shaniko and Antelope can be very simple. Shaniko is directly off of highway 97, and Shaniko is just 8 miles down the road.

The easiest way to get there from the Dalles, is to take Highway 197 to 97. Just be aware that there are many stretches of 197 that are very quiet and do not see much traffic. You could also take the route from the Dalles, to Biggs on Highway 84, and then follow Highway 97 to Shaniko.

From Sisters, Prineville, Redbone, Terrebone, and Bend, simply make your way to Highway 97 and follow that until you reach Shaniko.

To access Antelope, from the south, you can take Highway 97 and follow that until Highway 293, which will bring you directly to Antelope. You can also follow highway 97 into Shaniko and then turn onto highway 218.

From the north, follow Highway 97 to Shaniko, then turn onto highway 218, for direct access into Antelope.